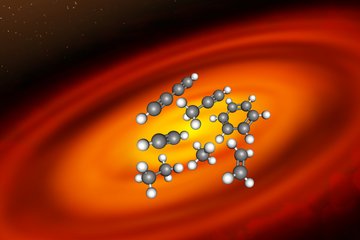

Three iron rings in a planet-forming disk

A three-ringed structure in the planet-forming zone of a circumstellar disk where metals and minerals serve as a reservoir of planetary building blocks

A research team, including astronomers of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), detected a three-ringed structure in the nursery of planets in the inner planet-forming disk of a young star. This configuration suggests two Jupiter-mass planets are forming in the gaps between the rings. The detailed analysis is consistent with abundant solid iron grains complementing the dust composition. As a result, the disk likely harbours metals and minerals akin to those in the Solar System’s terrestrial planets. It offers a glimpse into conditions resembling the early Solar System over four billion years ago during the formation of rocky planets such as Mercury, Venus, and Earth.

The origin of Earth and the Solar System inspires scientists and the public alike. By studying the present state of our home planet and other objects in the Solar System, researchers have developed a detailed picture of the conditions when they evolved from a disk made of dust and gas surrounding the infant sun some 4.5 billion years ago.

Three rings hinting at two planets

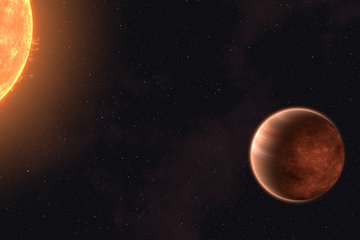

With the breathtaking progress made in star and planet formation research aiming at far-away celestial objects, we can now investigate the conditions in environments around young stars and compare them to the ones derived for the early Solar System. Using the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), an international team of researchers led by József Varga from the Konkoly Observatory in Budapest, Hungary, did just that. They observed the planet-forming disk of the young star HD 144432, approximately 500 light-years away.

“When studying the dust distribution in the disk’s innermost region, we detected for the first time a complex structure in which dust piles up in three concentric rings in such an environment,” says Roy van Boekel. He is a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany and a co-author of the underlying research article to appear in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. “That region corresponds to the zone where the rocky planets formed in the Solar System“, van Boekel adds. Compared to the Solar System, the first ring around HD 144432 lies within Mercury’s orbit, and the second is close to Mars’s trajectory. Moreover, the third ring roughly corresponds to Jupiter’s orbit.

Up to now, astronomers have found such configurations predominantly on larger scales corresponding to the realms beyond where Saturn circles the Sun. Ring systems in the disks around young stars generally point to planets forming within the gaps as they accumulate dust and gas on their way. However, HD 144432 is the first example of such a complex ring system so close to its host star. It occurs in a zone rich in dust, the building block of rocky planets like Earth. Assuming the rings indicate the presence of two planets forming within the gaps, the astronomers estimated their masses to resemble roughly that of Jupiter.

Conditions may be similar to the early Solar System

The astronomers determined the dust composition across the disk up to a separation from the central star that corresponds to the distance of Jupiter from the Sun. What they found is very familiar to scientists studying Earth and the rocky planets in the Solar System: various silicates (metal-silicon-oxygen compounds) and other minerals present in Earth’s crust and mantle, and possibly metallic iron as is present in Mercury’s and Earth’s cores. If confirmed, this study would be the first to have discovered iron in a planet-forming disk.

“Astronomers have thus far explained the observations of dusty disks with a mixture of carbon and silicate dust, materials that we see almost everywhere in the Universe,” van Boekel explains. However, from a chemical perspective an iron and silicate mixture is more plausible for the hot, inner disk regions. And indeed, the chemical model that Varga, the main author of the underlying research article, applied to the data yields better-fitting results when introducing iron instead of carbon.

Furthermore, the dust observed in the HD 144432 disk can be as hot as 1800 Kelvin (approx. 1500 degrees Celsius) at the inner edge and as moderate as 300 Kelvin (approx. 25 degrees Celsius) farther out. Minerals and iron melt and recondense, often as crystals, in the hot regions near the star. In turn, carbon grains would not survive the heat and instead be present as carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide gas. However, carbon may still be a significant constituent of the solid particles in the cold outer disk, which the observations carried out for this study cannot trace.

Iron-rich and carbon-poor dust would also fit nicely with the conditions in the Solar System. Mercury and Earth are iron-rich planets, while the Earth contains relatively little carbon. “We think that the HD 144432 disk may be very similar to the early Solar System that provided lots of iron to the rocky planets we know today,” says van Boekel. ”Our study may pose as another example showing that the composition of our Solar System may be quite typical.”

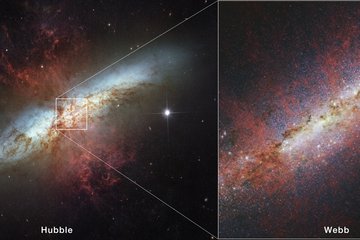

Interferometry resolves tiny details

Retrieving the results was only possible with exceptionally high-resolution observations, as provided by the VLTI. By combining the four VLT 8.2-metre telescopes at ESO’s Paranal Observatory, they can resolve details as if astronomers would employ a telescope with a primary mirror of 200 metres in diameter. Varga, van Boekel and their collaborators obtained data using three instruments to achieve a broad wavelength coverage ranging from 1.6 to 13 micrometres, representing infrared light.

MPIA provided vital technological elements to two devices, GRAVITY and the Multi AperTure mid-Infrared SpectroScopic Experiment (MATISSE). One of MATISSE’s primary purposes is to investigate the rocky planet-forming zones of disks around young stars. “By looking at the inner regions of protoplanetary disks around stars, we aim to explore the origin of the various minerals contained in the disk – minerals that later will form the solid components of planets like the Earth,” says Thomas Henning, MPIA director and co-PI of the MATISSE instrument.

However, producing images with an interferometer like the ones we are used to obtaining from single telescopes is not straightforward and very time-consuming. A more efficient use of precious observing time to decipher the object structure is to compare the sparse data to models of potential target configurations. In the case of the HD 144432 disk, a three-ringed structure represents the data best.

How common are structured, iron-rich planet-forming disks?

Besides the Solar System, HD 144432 appears to provide another example of planets forming in an iron-rich environment. However, the astronomers will not stop there. “We still have a few promising candidates waiting for the VLTI to take a closer look at”, van Boekel points out. In earlier observations, the team discovered a number of disks around young stars that indicate configurations worth revisiting. However, they will reveal their detailed structure and chemistry using the latest VLTI instrumentation. Eventually, the astronomers may be able to clarify whether planets commonly form in iron-rich dusty disks close to their parent stars.

Background information

The MPIA researchers involved in this study are Roy van Boekel, Marten Scheuck, Thomas Henning, Jacob W. Isbell, Ágnes Kóspál (also HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Konkoly Observatory, Budapest, Hungary [Konkoly]; CSFK, MTA Centre of Excellence, Budapest, Hungary [CSFK]; ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary [ELTE]), Alessio Caratti o Garatti (also INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy).

Other contributors are: J. Varga (Konkoly; CSFK; Leiden Observatory, The Netherlands [Leiden]), L. B. F. M. Waters (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; SRON, Leiden, The Netherlands), M. Hogerheijde (Leiden; University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands [UVA]), A. Matter (Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur/CNRS, Nice, France [OCA]), B. Lopez (OCA), K. Perraut (Univ. Grenoble Alpes/CNRS/IPAG, France [IPAG]), L. Chen (Konkoly; CSFK), D. Nadella (Leiden), S. Wolf (University of Kiel, Germany [UK]), C. Dominik (UVA), P. Abraham (Konkoly; CSFK; ELTE), J.-C. Augereau (IPAG), P. Boley (OCA), G. Bourdarot (Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Garching, Germany), F. Cruz-Saénz de Miera (Konkoly; CSFK; Université de Toulouse, France), W. C. Danchi (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, USA), V. Gámez Rosas (Leiden), K.-H. Hofmann (Max-Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Bonn, Germany [MPIfR]), M. Houllé (OCA), W. Jaffe (Leiden), T. Juhász (Konkoly; CSFK; ELTE), V. Kecskeméthy (ELTE), J. Kobus (UK), E. Kokoulina (University of Liège, Belgium; OCA), L. Labadie (University of Cologne, Germany), F. Lykou (Konkoly; CSFK), F. Millour (OCA), A. Moór (Konkoly; CSFK), N. Morujão (Universidade de Lisboa and Universidade do Porto, Portugal), E. Pantin (AIM, CEA/CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France), D. Schertl (MPIfR), L. van Haastere (Leiden), G. Weigelt (MPIfR), J. Woillez (European Southern Observatory, Garching, Germany), P. Woitke (Space Research Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Graz, Austria), MATISSE and GRAVITY Collaborations

MN